Frazier Family

Edited by Ann Chrissos

Henry J. Frazier (b. 22 Feb 1886, d. 27 Feb 1969) married Maggie Wash (b. 27 May 1902, d. 11 June 1989). They had eight children: Frieda, who died young; Marie, who married Robert Thompson; Arlene, who married Reuben Westfall; Clarence, who married Frances (last name unknown); Harold, who married Ella Mae McCullough; Clifford, who married Doris Fiddmont; Alice, who married George Works; and Geraldine, who never married. Clifford’s story is below. He worked as an overhead crane operator for Mississippi Valley Structural Steel and for Nooter Corporation.

The grandparents of Maggie Wash Frazier were William and Melinda Webster West. Their daughter Ida West married George Wash in 1881. They lived on Church Road in Westland Acres, where they raised their eight children: Mattie, Denia, Harry, Estella, Bertha, Alice, Robert and Maggie.

Judy Maschan and Cynthia J. Sutton produced three publications on these families: The People on the Hill; The History of the Union Baptist Church and the Residents of Church Road; and From Whence We’ve Come, 1987 and 1993.

Recollections of Clifford H. Frazier

By Clifford Frazier

My mother had a limited education, but she knew about history. My brothers and sisters and I sat and listened while she told us stories that her mother and her grandmother had told. She told us about our background and about Civil War soldiers riding through the area. We must pass those stories on to our children.

Our land came from my mother’s grandfather. He came to Chesterfield in 1797 with Daniel Boone and Lawrence Long. They brought fifty slave families from Kentucky and Virginia. They came up the Missouri River, and Daniel Boone took his slaves into St. Charles County. Lawrence Long stayed on this side of the river with his slaves, and that’s how my ancestors came to this area.

After my great-grandfather William West was freed from slavery, he purchased 343 acres from his slave owner. Polly Ellis, my great-grandmother on my father’s side, was only eighteen years old when she was freed from slavery, and she purchased 80 acres from her slave owner. There used to be a beautiful creek on her property where we all swam and fished. We called it Aunt Polly’s Hole. We had something unique, growing up in Chesterfield. Few blacks can trace their heritage back as far as we can.

I remember my first school. I was not enrolled, but in a little area like that, I could just go. I must have been around five years old when I started tagging along with my brothers and sisters. Our first school was called the Chesterfield School, and it was about five miles from where we lived. The whites had their Chesterfield School a little distance past ours. Then they started sending us to Glencoe School, eleven miles away, and we had to walk. My dad kept asking the school board to provide transportation, because the white children had a bus. Finally, Charlie Schaeffer’s daughter, Pearl, began driving us back and forth to school. About eleven or twelve kids would crowd into that automobile. The Schaeffers owned a lot of land out in this area, plus a tavern and a picnic area.

My dad’s name was Henry J. Frazier. He did a lot of farm work, because that was the only work that blacks could get out here. During the Depression he had two trucks, and he hauled rock for the WPA. He hauled rock for the construction of Babler State Park. All of that beautiful rock work in Babler Park was done by the guys of the WPA. A lot of blacks owned land where Babler Park is.

Our little church, Union Baptist Church, sits on a hill. There was always a lot going on at our church. We even sponsored fireworks on the Fourth of July. The men shot off skyrockets. It was gorgeous. And the older people put on great plays.

The whites had their things too. Madam Defoe owned a lot of land, and a lot of blacks lived on her property. They were servants. She held the Bridlespur Hunt. Everyone wore red coats, and they turned a fox loose and chased him on horseback. They had that every year, and blacks were included. We didn’t hunt, but we enjoyed the food.

My father was a great man. He enjoyed his children. He took us to things in the city: the Annie Malone celebration, ball games, and the fights. He played games with us until the wee hours of the night. My mother would say, “Henry, you let those children go to sleep. They’ve got to go to school in the morning.” My brother Harold was another inspiration. He was the leader of our little gang. He suggested all the games we played. And when we built our own sleds, or whatever we did, he was the ringleader.

When the WPA ended, people were looking for jobs. One of our white friends asked my dad if he would like a job in a factory. Mt dad said yes, so our friend got him a job at Mississippi Valley Structural Steel in Maplewood. My dad got me a job there, and I worked there for two summers, and then I was drafted when I turned eighteen.

When I went in the service, there were no black leaders. All of the officers were white. All of my leaders in the past had been African Americans. It was hard for me to comprehend whites telling that many blacks what to do. But I accepted it.

When I got out of the service I wanted to get my job back at Mississippi Valley Structural Steel, but they wouldn’t hire me. So I went to Tom Curtis, our Second District congressman, and he was very helpful in getting my job back. I think that was in 1950. I had been an operating engineer in the service, so I knew how to operate anything. I wanted to use the skills I had learned in the service. I kept asking the plant manager, “When is my time going to come?” After about seven or eight months he said, “oh, God damn, Cliff. Come on!” and he made me the first black operator of an overhead crane. From then on, I instructed every operator who came into that plant. Mississippi Valley Structural Steel was bought out by Bristol Steel, and when our plant closed, the Nooter Corporation asked three of us to come down here to work. We were the best operators in St. Louis. We could handle anything. I supervised the loading of all the railroad cars going out to San Francisco.

Life has been good to me.

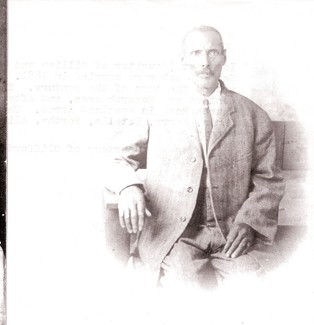

George Wash

George Wash, c. 1900. Courtesy of Clifford Frazier

Source

Clifford and Doris Frazier were interviewed by Jane Durrell and Arland Stemme on 30, October 1993.